Growing up is daunting. All those “rites of passage” through which we must travel. The first day of school, exams, dating, awkward holidays with distant relatives.

Speaking to young people I find that, even though some of that remains, important elements of childhood appear to be missing. The obvious is hobbies. What is a hobby but an interest with a passion? I’ve come across few kids lately who have a passion for anything.

Another missing component is a sense of wonder.

My mother was born in 1901. Once, in a single lengthy conversation, she told me about the wonder of her first plane ride, taken as a daring young woman with a barnstormer at a state fair for the princely sum of $3 … the first time an earphone was held up to her head and she heard KDKA coming through the ether … the first picture on a hand-built TV set that my father assembled in the late 1930s … the wonder of power and the telephone finally coming to her village in upstate New York.

I don’t encounter kids who wonder at the iPod, who are more than blasé when they travel the Internet.

We who are over a certain age can recall our share of youthful events and circumstances that precipitated a wonderful excitement. One of the more vivid was the appearance of the transistor radio.

Nobel trio

How did the transistor semiconductor get to the portable radio?

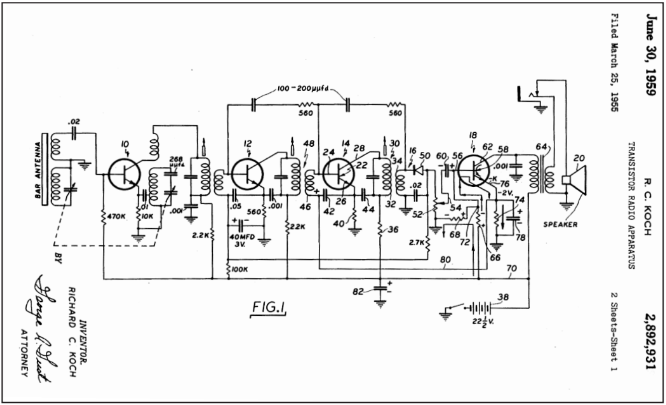

Whether you believe that the transistor was created out of reverse Roswell engineering or painstaking research at Bell Labs, its introduction in the early 1950s constituted an electronic revolution. Bell Labs’ focus had been on innovations related to communications, and the transistor was no exception. Its goals, among many, were to identify a new device that would reduce power consumption and hence heat — the destroyer of electronic gear — to lower the noise and hence the distance and stages through which a telecommunications signal could pass, and to increase reliability.

Tubes were the gain device of the day and were even used deep in the ocean on transoceanic cables to make up the loss of hundreds of miles of wire. But as marvelous as the tube was, something new was needed.

Each little research step came together when research scientists John Bardeen, Walter H. Brattain and William Shockley successfully regulated a larger current flow by introducing a smaller current flow into a “semiconductor” junction, essentially creating a current amplifier.

This basic action is the essential fundamental property of all transistors, and everything after was refinement. The three received the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics for inventing the transistor.

But the basic maxim “It’s not what you got but what you do with it that’s most important” applied. It’s interesting that one of the first applications envisioned for the transistor was a compact portable radio.

Bell licensed transistor technology to other companies; one of these was Texas Instruments, which made the transition from prototype to product, offering workable transistors to the electronic industry. TI wanted to sell these “solid-state” devices but needed not only to create circuits and consumable products that used them, but also to capture the imagination of engineers to get it done.

The outshoot was a prototype portable radio. A thrilling breakthrough idea, but only one small manufacturer took up the product coming to mass market. It was Regency, with its model TR-1, introduced on Oct. 18, 1954, at a price of $49.95, roughly equivalent to $400 today.

This opened the flow gates of demand. The descendants of this little gem are still for sale everywhere.

Personal

These little units were more exciting than most innovations. They converted a communal experience to a personal one.

Prior, radios had been found mostly where many people could listen: living rooms, family cars and the like. The decision about what was on and when to listen was determined not by kids but by elders or at least older siblings.

Listening could now move away from parental control to far-flung places like under the covers late at night, out riding our bikes and during recess at school. A universal accessory to most transistors was a simple earphone that went directly into the ear and needed little level to be audible, making it the most intimate of experiences.

Radio was talking directly to you.

In retrospect we wonder whether transistor radios gave rise to rock and roll, or the reverse. The phenomena appeared pretty much contemporaneously. But the times were changing and new, exciting, challenging music played through these receivers.

As a business, radio responded not only to the new youthful audience with the music they wanted to hear but to the new consumers and their distinctive advertising needs, a unique conduit that TV had difficulty duplicating.

On the technical side, the transistor radio gave the ultimate personal mobility to radio. In my own travels as a Boy Scout far beyond power and “civilization,” I listened to KOMA late at night at Philmont Scout Ranch in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of the Rockies, or WWVA under the stars canoe camping on the wild rivers of West Virginia.

Adults made use of transistor radios, of course. I can tell you from experience that you couldn’t get anyone’s attention in Baltimore during the 1966 World Series, thanks to all the transistor earphones in use.

Just as the All American Five radio we discussed in an earlier issue garnered more ears for radio by increasing the locations and counts of sets, the portable transistor took radio more directly to the ears and set the ears free to roam.

What a wonder!