The author’s new book is “Beyond Powerful Radio — An Audio Communicators Guide to the Digital World.”

She devotes a chapter to emergency preparedness. This is an edited excerpt.

Imagine the worst — the recent L.A. wildfires, an earthquake, a blizzard or tornado, a school shooting. If a radio station has limited news staff, and most of the programming is AI, syndicated or voice-tracked, how will you serve your audience if lives are in danger and there’s a fast-moving tornado or a toxic spill?

In the United States, stations have failed the public in its time of need. And without advance preparation it could be your city, your station and your listeners.

The answer is to prepare for anything that can happen. Have a contingency plan in place so that all members of your staff know what to do when an emergency event occurs.

The very best solution would be to bring back reporting and news coverage. Many of the program directors and managers I work for would be only too happy to restore full-service news departments to their stations, but if they don’t have that option, then what?

As mentioned, broadcasters are depending, more and more often, on artificial intelligence. AI is already scraping data from government departments like the United States Geological Service, to generate automatic emergency announcements. These go straight to the EAS. You may already get these types of alerts on your phone. AI is likely to be more widely used and generate more detailed announcements as it improves. And it will help. Would you, as a listener, care if you hear the first alert about an emergency from a newsroom or AI delivered straight to your speaker, as long as it told you what you have to do?

But even if AI were perfect, in a disaster, the announcement may not make it to stations or listeners’ phones. In Hawaii, during the Maui wildfire of 2023, AI-generated announcements were transmitted via cellphones — but the inferno had devastated the cellphone towers. Radio stations were still operating, and, if they had had news people on site, they could have helped deliver potentially lifesaving warnings.

With these real-life experiences in mind, what can broadcasters do to serve their cities on the inevitable day when their communities need critical information?

Even with a small staff, by using a little creativity and pulling together during a crisis, there are some practical ways you can get information out to the public.

Alan Eisenson programmed a cluster of stations in Sacramento, Calif., including news leader KFBK, and talk stations in San Francisco. He lived with the reality of a news staff that was a lot smaller than it once had been.

Still, Eisenson prepared, because “Even if you have a skeletal news staff, when events happen, and calls start pouring into the station, the receptionist or board op or webmaster is overwhelmed, and the GM yells ‘Do something!,’ you have to have a plan.”

Partnering with TV

Jerry Bell, who spent decades as the news manager of KOA Radio in Denver, Colorado, and Lee Harris, an executive at NewsNation, a former station owner and 1010 WINS New York newsman, agree with Eisenson on this: You should form a partnership with your local TV news station or digital news services. Do it now.

One of the goals should be to set up your station so that your local TV news team can send its audio feed directly over your airwaves, to your entire station group, including your music stations.

Eisenson also suggests partnering with other radio stations in your market, including your competitors, in times of dire crisis.

Since you can’t predict whose transmitter will still be functioning in certain types of emergencies, “arrange in advance for any stations in your cluster or area that have news staffs to record reports for stations that don’t. Have them sent by any method you can get onto your airwaves. You may need to use all of your frequencies to disseminate life-saving information.” Offer the same courtesy to your local TV partner.

“And it’s vital that you teach your staff, from the all-night automation supervisor to the front-desk receptionist, how to flip that switch to halt your automation or a show in progress so you can go live, or change over to a live feed from your TV partner.”

That’s not all you’ll need to teach your day-to-day operations people. Everyone in your building can learn to handle an emergency news situation, should one arise. Just as you train for a fire drill, practice a news drill with everyone in your company so you’ll have “all hands on deck” when you need them.

The basic things your staff should know, in case of emergency:

- How to maintain credibility in order to collect, gather and verify that information is correct before it goes to air

- How to get in touch with local authorities on the scene who can give you credible information

- What is the right time and place for listener calls

- What role should social media play in disaster or major event coverage

- How to turn off any automation, take over the controls and broadcast live

Make sure your staff knows that broadcasters need to adhere to the first rule of the Hippocratic Oath, given to all new physicians: “Do no harm.”

Credibility and correct information are vital. If someone calls and tells you it is safe to go into a building where a shooting took place, but it turns out one of the gunmen is still inside, you may have made the situation worse. If you broadcast the wrong information, such as reporting on the death or injury of a person who is neither dead nor injured, you cause unnecessary pain and suffering to their families. And there are legal issues.

This is why extra caution should be used when giving names of people affected by a disaster before they have been officially confirmed.

Rita Rich, president of Rita Rich Media Services, worked with the Red Cross as a client. Experienced in producing national talk shows, Rich has also worked network newsrooms. She maintains you can train just about anyone on your staff to give accurate information in a crisis.

“Teach your station’s staff how to interrupt regular programming and turn on a microphone. In an emergency you will need everyone you’ve got. If you have a very small operation, a ‘Board Op 101’ training seminar should be part of the station basic employment orientation. Make certain everyone on your staff is familiar with news and press releases. Everyone should know where your emergency contact book is located.”

Rich suggests assembling a physical book of essential contacts, with e-mail addresses and text and phone numbers to call, should the computers go down in an emergency. These contacts are especially important to have:

- County emergency operations center if you have one.

- Local sheriff’s department/police department.

- State police barracks numbers.

- Fire and rescue media relations/public affairs office direct, mobile and home numbers, and social media contacts.

- Department of Homeland Security numbers.

- Emergency contact numbers for public information officers of high-profile locations such as airports, seaports, power plants and utilities.

Rich says your book should also have information on where people will be able to find help. Have contacts for your local Red Cross Chapters and their emergency operations centers. Include first-responder citizen support groups such as the Salvation Army, and local shelters for people and even animals. There may be people unwilling to evacuate in a crisis if they fear for their pets. (Emergency volunteers are a good source of leads for stories. However, most will not be authorized to speak “on the record.”)

If you do not have your own weather expert, know which local weather services your station or group ownership works with. Have the number of governmental offices that handle weather-related emergencies.

Have contact information of local hospital emergency rooms and hospital media relations/public affairs personnel, to find out about casualties.

While instant messaging and other forms of social media can be useful, Rich warns the information must be verifiable.

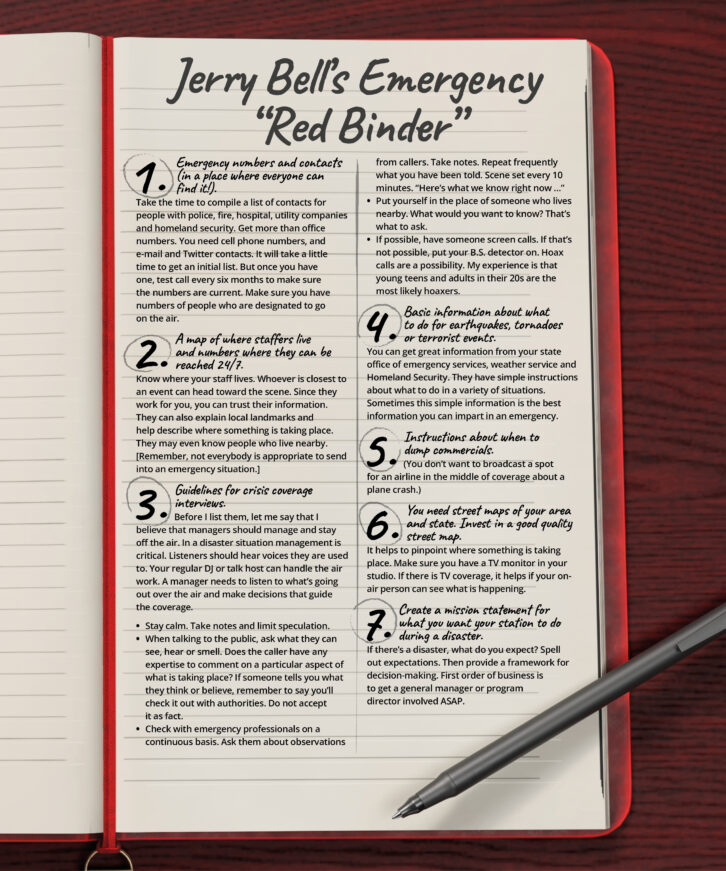

Jerry Bell recommends that you keep a “how to” guide in your studio for emergencies: Have a plan. Keep it in a red binder marked “Emergency” in your studio. You can also put it on a computer, but what happens when the power goes out? Also, you can tear pages out of a binder if you need to.

A lot of stations already have a printout and/or a computer file of emergency contact phone numbers including cell numbers of firefighters and police, FBI and FEMA. But it’s useless unless everyone in the building knows how to get hold of it. Copies of the emergency plan should also be in the general manager’s office and the program director’s office.

The emergency chapter of Geller’s book also discusses press passes, emergency scripts, staff training and other aspects of this important topic.

Text from “Beyond Powerful Radio” is used with permission from Routledge Press © 2025 Valerie Geller.