Broadcast management and engineering deal with countless moving parts and people. Anyone in the broadcast world can attest to seeing a GM in a sales meeting one minute and heading out to a remote broadcast the next. The engineers are busy with IT tasks, transmitters, studios and fixing toilets.

While on-air presentation is basically what we “do,” the question is: What is tangible about our line of business? What is most at risk? The answer is, the station license. It is, quite literally, everything.

The license from the FCC does far more than hang on the studio wall. It is the document that says a broadcast entity has the legal right to occupy a specific part of the government-regulated broadcast spectrum. We should be reminded that the government has unfettered oversight concerning the legal operation of a broadcast plant. While it’s no secret that a random FCC inspection is a potentially gut-wrenching experience, there are reasonable steps that management and engineering can take that will ultimately protect the station license.

ANTENNA REGISTRATION

Jim Dalke, the administrator of the Washington State Association of Broadcasters Alternative Broadcast Inspection Program, served as an ABIP inspector in the state for 10 years.

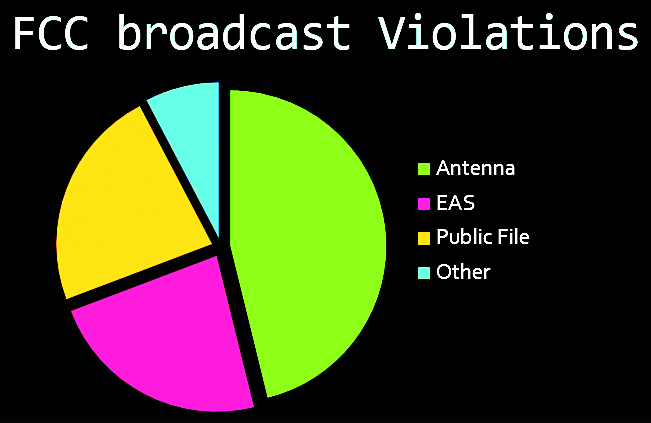

He found that one of the most common regulatory infractions uncovered by inspectors centers around antenna registration requirements. For example, a station is held responsible for proper tower painting and lighting regardless of whether the tower is leased or owned by the station.

[In Washington State, Celebrating AMs’ FM Translators]

The station is most certainly responsible for correct signage and fencing. Dalke encourages stations to keep tower sites mowed and clean. An inspector will appreciate a well-kept tower site.

Other common inspection problems include improper power monitoring (especially for TV and AM broadcasters) and improper EAS monitoring assignments. Logging of missed sent and received tests is important.

The public file must be in order. However, the recent ruling that public files be kept and made available online has forced stations to do better, and Dalke indicates that public file infractions are far fewer of late.

In the past, many stations kept a copy of Title 47 of the Code of Federal Regulations, in the facility. This has become unnecessary as CFR 47 is now available online for quick access and reference.

THREE STEPS TO TAKE

In his presentation at the NAB Show called “Protecting the FCC Station License,” Dalke suggests that there are three key considerations.

The first is proper installation of a qualified Designated Chief Operator. The DCO, most commonly a chief engineer, is an employee or contractor who can knowledgeably execute FCC regulations. At a time when full-time engineers may be hard to keep on the payroll, a contract engineer can equally serve as the DCO. The key is that the DCO knows the broadcast operation well, is aware of and able to implement FCC regulations properly and can effectively guide an FCC inspector through the facility during an inspection.

The second key component is satisfactory completion of the FCC Self-Inspection Checklist. The checklist is available for easy download and has specific sets of requirements for AM, FM, TV, LPFM, translator and booster stations. Caution, the FCC Self-Inspection Checklist is not exhaustive and indeed parts of it are out of date. It will, nonetheless, allow the broadcaster to address the most frequently violated broadcast regulations. The checklist is best completed by the DCO.

The third key component that will help protect the FCC license from regulation discrepancies is to enroll the station into the Alternative Broadcast Inspection Program. ABIP is provided by most state broadcast associations. Scheduling an ABIP inspector is, by far, more settling than undergoing an actual random FCC inspection. It is not a free service, but well worth the quick application process and financial investment.

WHAT TO EXPECT

The ABIP inspector is a qualified engineer who is approved by the regional FCC field office. The inspector comes to the facility at a scheduled time and generally spends four to six hours going over items specific to the Self-Inspection Checklist and CFR 47.

The inspector will review his or her findings with the chief operator and management and suggest avenues to take that will lead to a successful FCC inspection should that day come. As opposed to a real inspection, the ABIP inspector will allow a reasonable amount of time (as much as 90 days) for the station to resolve its compliance problems.

Once everything checks out, the station will receive a Certificate of Compliance and will be immune from random FCC inspections for three years.

However, there are caveats. First, the inspector generally will steer clear of inspecting lowest unit rate, EEO compliance and RF radiation exposure measurements. Inspectors will take only a cursory look at the online public file. Finally, the ABIP will not insulate a broadcaster from an FCC inspection that results from a filed complaint.

Broadcasters may not be necessarily aware of their FCC license value. Without it, they are out of business. The license represents trust granted to the broadcaster by the FCC, and in order to keep that trust, there are rules to be followed. As humans we are bound to miss some of those rules, whether through complacency or pure accident. The best ways to be ready for an FCC inspection are actually very simple. Have the right people in place and go through the paces with the Self-Inspection Checklist and ABIP.

Chris Wygal is a radio engineer and Radio World contributor.