In a moment of insanity, your brother has loaned you his ’61 Impala 409 pearlescent red convertible.

It’s a sunny Maryland Sunday in the summer of ‘64 and you’re tooling back from the drag races. The top is down, WCAO is up and rocking on the radio, and the twin 6-by-9 oval speakers in the dash and rear console are just keeping up with the wind noise.

Capture the magic moment. Your girlfriend du jour is eternally young in your mind’s eye, and Chuck Berry’s exhortations of ‘hail, hail rock and roll’ will always be in your heart.

A fruitful marriage

Playing the radio while you moto-vate was a wonderful thing, allowing you to be internal and external at the same time.

You could make the music a personal experience, even singing along in the privacy of your mobile suite or be carried afar by the drama programs or news reports from around the globe. Amazing sound could come from those speakers. You were never alone.

Radio is still that way.

The marriage of automobile and radio seems so logical, one can only wonder why it took the intervention of entrepreneurs to make it happen. Happen it did; and nearly 80 years later, radio and the auto remain joined at the hip.

The seminal year was 1929. After failing twice in the storage battery business, Paul Galvin was encouraged to try to put a workable car radio into volume production, an idea that had pretty much been ignored by auto manufacturers.

In retrospect, the problem required a system solution that eventually involved three steps: a suitable, sensitive receiver; getting that receiver to work on the erratic electrical supply provided by the car; and overcoming ignition and tire static noise.

In 1901 Marconi had put a radio into a steam-powered car (at least this eliminated ignition noise!), but since his radio took up most of the car, the idea didn’t catch on.

After-market

Galvin needed a solution to match his vision.

He turned to an innovator who had imagination and what would now be described as “outside the box thinking.” His perspiration and perseverance didn’t hurt either.

That fellow was William Lear, whose name lives on in a jet, one of many products spawned from his 120 or so patents. Lear solved much of the car radio challenge and sold Galvin the patent (U.S. patent 1,944,139).

However, even with a workable product, the car radio was far from an overnight success.

This “after-market” automobile item was first sold to accessory marketers, who would then sell it to customizers, who would finally install the radio in the car.

Over the next few years Galvin took over the direct marketing to installers as sales grew. He knew that his product needed differentiation in the marketplace as competitors entered the field.

A special trademark came to him while shaving: “Motorola.”

He hoped this brand name could capture the imagination of customers, bringing to mind images of motoring along with the joy of a radio.

That joy was spreading; by 1934, total industry sales of car radios topped $1.35 million. During the 1930s the car radio business dominated the Galvin output so much he eventually renamed his company after the trademark.

Popular cars at the time cost about $500; a radio to be installed in that vehicle, such as the Motorola model 5T71, cost about $130. So after custom installation, a radio might well cost half the value of the auto.

Tick-tock

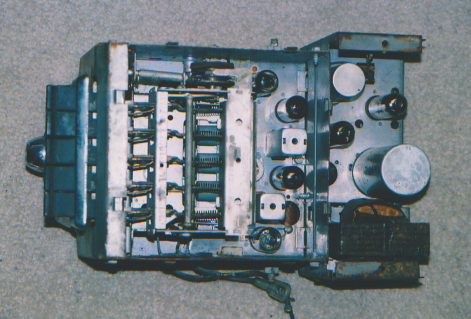

Early car radios from the majority of manufacturers resembled regular tube sets with progressive refinements. Most used the car battery to light the filaments and a vibrator B+ supply.

The vibrator was a small pendulum-type affair in which a paddle arm, hinged at one end, would oscillate back and forth, sort of like a high-speed metronome, reversing the battery voltage into a step-up transformer primary.

Thus the designers had created essentially a ragged square wave. Eliminating this “vibrator noise” both electrically and acoustically, a new phenomenon, begat its own series of problems and unique solutions.

As designs evolved, a de rigueur first RF stage appeared to increase sensitivity to reduce fading and make a better match to the antenna. An automatic gain control system, sometimes both on the RF/IF stages as well as in the audio sections, were added by engineers to reduce variations in the audio output of the speaker.

Inside the car, the electrical system, generator, distributor, spark plugs and so forth were all big sources of interference and noise. Special high-resistance spark-plug wires, bypass capacitors and other devices were developed and applied to attenuate their noise competition with the radio signals.

Tires were a problem as well, acting like four Van de Graaff static generators. Special powders were developed to be injected in the tires, and static drain straps were installed to siphon off any static charges and bring the auto itself close to ground potential.

Vibration in autos was and is a large engineering challenge. Tubes in the 1930s were usually built in the “octal” push-in format. These actually could be driven from their sockets by vibration, so radio manufacturers devised various cushioning restraint systems until the introduction of a full series of tubes in the “loctal” format, where the metal center indexing pin had a “catch ridge” that would hold the tube securely in its socket.

Miniature tubes had less mass and could be restrained by their own pin friction; these found their way into car radios in the late 1940s.

A new series of “12 Volt” tubes appeared in the mid-1950s along with the first transistors used in the audio output, together eliminating the need for B+ and with it, the vibrator.

All-transistor radios followed shortly.

Push it

Even before text messaging and cellphone use in the car, tuning the radio was deemed a hazardous distraction. Pushbutton pre-selection of stations was introduced by Motorola in 1937 to make tuning a no-brainer, one-finger action.

The setup tuning of these pushbuttons can be divided into two schemes.

The earliest was a series of separate LC networks, one for each station. My Chrysler car radio — the same model that Bette Davis tunes in her coupe in the 1939 film “Dark Victory,” and which I had modified to run on 120 Volts AC — had little finger wheels for tuning behind each button, accessible when you pulled the button cap off.

Later a mechanical indexing system was devised for pushbutton operation that positioned both the tuning dial and the main tuning element (cap or inductor) that set the frequency. Ordinarily a station was tuned in, then the button allocated to that station was pulled out and then pushed back in, fully memorizing the mechanical setting.

Broadcasters picked up on pushbuttons and station loyalty; they started urging listeners to make their station “the number one button on their car radio!”

The first appearance of the “signal seeking” radio was in the early 1950s, with two unique wrinkles.

Most of these radios had a switch marked “Town and Country,” to set whether you wanted the radio to find only local stations or any receivable signal.

A second innovation was a switch under the carpet for the left foot that would be depressed by the driver momentarily (we don’t want to add to the distractions). A little motor would start tuning the radio up the dial. The AGC circuit in the radio would tell the motor to stop on the strongest or any station depending on your town/country choice.

Simple joys

In the United States, GM introduced the first factory-installed, “in-the-dash” radio in 1936. From the postwar period on, most consumers bought their car radio with the car.

By the 1980s nearly all auto manufacturers provided at least a manually tuned AM radio as standard equipment. Some of these radios used ASIC LSI ICs, and an acceptable radio could be made of just a few chips. Including the radio cost the manufacturer only a few dollars more than placing a matching dash plate over an empty hole.

In the digital tuning age, many of these early features are still with us, including pushbuttons (now just accessing digital memory registers) and signal seek.

Most new radios have an interesting refinement: If in seeking they find no local stations, they automatically step down to accept a lower signal strength, a useful feature in some of the remaining great outback of America.

As our time spent in automobiles increases thanks to traffic congestion and longer commutes, our time spent involved in mobile audio is going up too.

Some sound aficionados find factory-standard gear to be lacking and will spend thousands on “sound tuning” upgrades. Choices on the listening side are changing as well, thanks to satellite radio and HD2 channels, which can deliver traffic reports and information focused on commuters and provide more options and useful data to drivers than ever imagined possible.

But no matter how high tech, the simple joy of a pleasant audio companion in the car, a pleasure that stimulated radio sales at their introduction 80 years ago, is still there.

Research for this article came from a number of sources including the official history of Motorola, the Powerhouse Museum of Australia and the American National Business Hall of Fame.

Buc Fitch wrote in October about the GE Phasitron FM transmitter. Past Milestone columns are archived at radioworld.com. E-mail the author c/o Radio World at radioworld@imaspub.com. If a reader needs help converting a vintage car radio for use out of the car, contact the author.