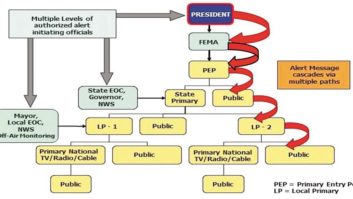

The caption for this image on FEMA’s website notes that the Emergency Alert System “is used by alerting authorities to send warnings via broadcast, cable, satellite and wireline communications pathways.” Should alerts be issued in languages other than English? WASHINGTON —The idea of transmitting EAS messages in languages other than English has been discussed at the Federal Communications Commission for nearly 10 years. Now broadcasters, alert originators and public interest groups are among those giving the commission opinions about how to accomplish “multilingual EAS.”

The nonprofit Minority Media Telecommunications Council first petitioned the agency about multilingual EAS after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The organization suggested that the commission explore how emergency alerts could reach people who do not speak English as a first language, or at all, during times of crisis. Among other things, it called for cooperation between broadcasters and others in the alerting community on the issue, including a mandate that broadcasters provide translation. The Independent Spanish Broadcasters Association and the Office of Communications of the United Church of Christ joined the petition.

Since the 2005 petition, the commission twice asked for public comments on multilingual EAS but had not implemented any rule changes.

The MMTC and other public interest groups prodded new Chairman Tom Wheeler about the issue at the end of last year; and in March, the FCC’s Public Safety and Homeland Security Bureau sought to refresh the record on multilingual alerting, citing subsequent changes in EAS including the transition to Common Alerting Protocol. The bureau asked for comments on MMTC’s petition.

MMTC proposed that the commission change its EAS rules so that Primary Entry Point stations would be required to air presidential-level messages in both English and Spanish. It also proposed that FCC rules ensure that local and state EAS plans include a Local Primary Spanish (LP-S) designation and — where a substantial portion of the population speaks languages other than English or Spanish — a Local Primary Multilingual (LP-M) designation.

The MMTC also suggested the commission adopt a “designated hitter” approach for situations when an LP-S or LP-M station cannot transmit EAS down the daisy chain. The nonprofit envisions that broadcasters and alerting agencies would determine — before a crisis, as part of a wider emergency plan — which station in a market would be the “designated hitter.” That station would air emergency information in other languages “until the affected LP-S or LP-M station is restored to the air,” according to MMTC. For example, “one market plan might spell out the procedures by which non-English broadcasters can get physical access to another station’s facilities to alert the non-English-speaking community,” such as where to pick up a station key.

In the past, broadcasters have raised concerns that a designated hitter approach would require stations to retain employees who could translate emergency information in the language of the affected station. MMTC, though, believes designated hitter stations “could simply allow access to the employees of the downed non-English station. These employees, in turn, would be responsible for providing non-English EAS alerts” to the public, according to the FCC. It asked for public input on this view, as well as on costs.

Previously, broadcast/cable industry representatives have argued that originators of alert messages, which are typically local and state government agencies, should bear the responsibility for issuing multilingual alerts. They’ve said it would be impractical for stations to generate timely, accurate alert translations, according to the commission.

The agency in March asked for updated comment on that, and sought input on other proposals. It also asked for comments about the availability and cost of technical solutions for multilingual EAS, such as text-to-speech translation software.

Initial comments were due to EB Docket No. 04-296 by May 28 and replies by June 12. Some 14 comments had been filed in the latest cycle as of early June. What follows are excerpts of the major themes. Topics are grouped by subject, so certain commenters appear more than once.

PLAN SHOULD BE REQUIRED

Minority Media Telecommunications Council:

At its core, MMTC’s most recent request — requiring broadcasters to work together with state and market counterparts to develop a multilingual plan that communicates each party’s responsibilities in reasonably anticipated emergency circumstances — is a simple request that would help to ensure that non-English speaking populations receive timely access to both EAS alerts and non-EAS emergency information.

“DESIGNATED HITTER” MODEL CAN WORK

MMTC:

[N]ews outlets and broadcasters have considerable experience working with each other and sharing information in extenuating circumstances. … While translation technology exists, it is not yet capable of capturing the nuances of language through which critical information is transmitted, making it essential that a real person convey lifesaving information in a variety of languages. Under the designated hitter model, multilingual messages should be translated at the point of origin or broadcast by a live person, since language software may confuse the meaning or intent behind a specific translation.

NEXT NATIONAL EAS TEST SHOULD BE PRIORITY

Fifty state broadcasters associations, including those of the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico:

Conducting a second national EAS test should be the federal government’s top priority for fear that multilingual EAS alerting may complicate matters at a time when “getting it right” in English should be the first priority of our nation.

The state associations strongly oppose, for First Amendment and other reasons, the imposition of any direct, or indirect, requirement that an English language radio or television broadcast station air emergency information in a language other than in English, or for that matter, that a foreign language radio or television station air emergency information in a language other than the language of its general format.

MAKE “DESIGNATED HITTER” APPROACH VOLUNTARY

NAB:

Federally mandating the creation of “emergency communications plans,” such as the proposed “designated hitter” approach, is unnecessary to ensure the continued delivery of emergency information, including non-English programming. First, broadcast markets have changed since the time of the Hurricane Katrina disaster that prompted the designated hitter proposal. It is extremely unlikely that another emergency will occur when the only non-English station in a market is rendered inoperable. There has also been significant growth in the number of Spanish language stations since Katrina hit in 2005. …

In addition to market changes, evidence shows that voluntary cooperation among local stations, combined with commission processes created since 2005, such as the Disaster Information Reporting System, will ensure continued emergency programming, including non-English information, without federally mandated emergency communications plans suggesting a particular approach to local collaboration.

Fifty state broadcasters associations:

The state associations do support the concept of “designated hitter” compacts in which station licensees choose voluntarily to enter into formal or informal arrangements with each other, under which one station would agree to provide emergency information coverage also in the language of the other station, in the event that the other station’s on-air operations were interrupted during an emergency. For that reason, MMTC’s proposal does warrant careful consideration by the various state and local emergency management authorities, working with their local broadcasters and other communications providers to determine the feasibility of such compacts on a voluntary, case-by-case basis.

MAKE MESSAGE ORIGINATORS RESPONSIBLE FOR MULTILINGUAL EAS

NAB:

Primary responsibility for the distribution of multilingual EAS alerts should lie with the government and emergency management authorities that originate such messages. Earlier commenters agreed that originating multilingual alerts from a centralized point would be much more efficient than requiring thousands of individual EAS participants to translate messages before relaying them to the public.

National Cable Television Association:

As we and others have put forth in the past, the practical solution to providing multilingual EAS is for EAS message originators, whether federal, state or local government entities, to issue dual-language messages in English and Spanish (or another appropriate language) for emergency alerts in appropriate communities. As the commission points out in the Notice, broadcasters and cable operators agree that the “responsibility for issuing multilingual alerts must rest with alert message originators, and that it would be impractical for EAS participants to effect timely and accurate alert translations at their facilities.”

Adrienne Abbott-Gutierrez, filing as an individual with experience with Nevada SECC, and broadcast engineer, reporter:

Nevada’s foreign language stations include approximately 30 Spanish and two Chinese broadcasters. … Many of these stations are fully or partially automated and only a few have a news department. Station managers tell me that they would have to be staffed 24/7/365 to carry EAS tests and messages in their language and that is beyond their budgets. They do acknowledge that having the text of the EAS message available through CAP will allow them the ability to translate the information on their own when activations are made during the hours that they are staffed.

The Las Vegas office of the National Weather Service offered several years ago to install a NOAA Weather Radio transmitter for Spanish-language weather information if the broadcasters were able to raise the $10,000 needed to buy and install the transmitter. The cost per station would have been approximately $2,000 each but the stations responded that they could not afford the price.

There has been agreement here among our Spanish-speaking stations that an LP Spanish is needed. However, none of the stations feel they can fill that role because they lack the staff. …The apparent lack of interest and commitment to foreign language EAS at the individual station level can only mean that there is not a lot of demand for translations.

CAP EAS CAN HANDLE it, BUT GEAR MAY NOT

Federal Emergency Management Agency, Integrated Public Alert and Warning System Program Management Office:

FEMA supports the work of MMTC to extend alerting to the non-English speaking population. The U.S. IPAWS Common Alerting Protocol profile specifically includes specified means and methods to propagate alert information received with multiple language versions to privately held broadcast, cable and commercial mobile service providers for delivery to members of the public using their systems. Alerting Authorities may originate alert messages in the language that they prefer for consumption by the public or other public warning dissemination and distribution methods. However, AAs should understand that some EAS encoder/decoder products may have limitations in text-to-speech conversions to languages other than English and compose messages intended for text-to-speech accordingly.

EXEMPT NCE STATIONS

Educational Media Foundation:

NCE stations perpetually operate with limited resources to carry out their sometimes broad nonprofit mandates. … NCEs simply do not have the resources to provide for a simultaneous translation staff to be on call 24 hours a day, 7 days a week in order to step in as the “designated hitter.” …

EMF requests that the commission either exempt noncommercial broadcasters from any new regulations promulgated to require the provision of multilingual EAS alerts, or allow these stations to opt out of any “designated hitter” rule that may be adopted.

LIABILITY ISSUE?

Adrienne Abbott-Gutierrez:

The “designated hitter” approach proposed by the MMTC and others presents a number of concerns. In addition to finding ways to alert the non-English speaking population to tune to the appropriate station, one manager asked me how he could be sure that a person speaking a language he didn’t understand was actually presenting useful emergency information or inciting the audience to riot and what that meant as far as his ability to retain control over his airwaves. [N]one of the managers I questioned approve of the idea of giving keys and station access to a non-employee, even an employee of another station.

INCLUDE SIGN LANGUAGE

Wireless Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center, Center for Advanced Communications Policy, Georgia Tech:

There currently exists a great need from the deaf community for [American Sign Language] interpreted messages of government issued emergency alerts. … These alerts are most often delivered through sound and text, though this provides many challenges for someone who relies solely on ASL.

For example, a local television news station reporter may verbally deliver a message on an approaching severe storm, but this audible message is not accessible to a deaf person. There are several incidents in which this inability to receive accessible information during emergencies can become a problem. One research study found, anecdotally, a deaf man who, in the midst of a tornado warning in Oklahoma, resorted to lip reading (to the best of his abilities). He only understood one word, “closet,” which was the difference between him taking protective action or being completely unprepared for the impending tornado.

Comment on this or any story. Email radioworld@nbmedia.comwith “Letter to the Editor” in the subject field.