The nation’s emergency alerting system has evolved dramatically over many years, but few stakeholders believe the system is perfect or that its evolution is complete.

The nation’s emergency alerting system has evolved dramatically over many years, but few stakeholders believe the system is perfect or that its evolution is complete.

Now the Federal Emergency Management Agency has a series of 14 well-vetted recommendations from its own National Advisory Council, about how to improve the reach and reliability of IPAWS, the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System.

“As IPAWS moves into the future, FEMA must continue to promote the integration of alerting into existing and new dissemination technologies,” said the NAC in a report issued in February called “Modernizing the Nation’s Public Alert and Warning System.”

“It must expand IPAWS reach into the special needs and multilingual communities, and support multimedia presentation, while maintaining the capability to deliver simple text and audio when and where needed.”

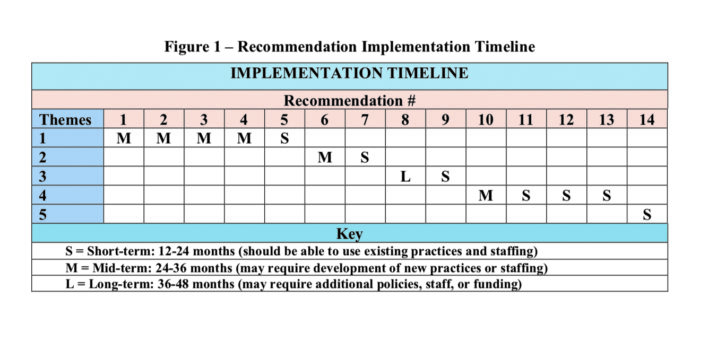

The report released a total of 14 proposals broken into five themes that targeted specific areas of concern and opportunities for improvement. Those key areas include:

- Improving alerting authorities’ ability to transmit effective alerts

- Improving public and congressional understanding of emergency alerting

- Optimizing technology

- Identifying and adopting current and future technologies and

- Initiating cross-functional management and administration of IPAWS

Each recommendation also included a timeline for estimated implementation and a checklist of things to consider.

[Advisory Group Issues Recommendations for Improving IPAWS]

It’s probably no surprise that the theme with the greatest number of suggestions was how to go about improving an alerting authority’s ability to transmit an effective alert.

“These recommendations create a set of standards for alert originator training and certification with annual updates, so preparation and resources are current and consistent,” the report said.

The NAC team suggested the creation of a centralized ’round-the-clock help desk with cross-functional tools and best practices for both new and experienced originators.

According to the report, the first priority for the IPAWS system is that it easily allow an alert originator to develop timely alerts that will allow members of the public to take appropriate protective actions. As a result, the NAC team offered suggestions on core message characteristics — thinking about the way the message is presented, how such a message can be cancelled or updated and how originators can quickly report false alerts.

That led to proposal number two: The suggestion that FEMA should develop multijurisdictional templates for alerts and warnings that will offer provide guidance and best practices for emergency alerting.

[Next Nationwide Test Set for August 2019]

“These recommendations create a set of standards for alert originator training and certification with annual updates, so preparation and resources are current and consistent,” the authors wrote.

Among other recommendations under this theme are suggestions that FEMA work with stakeholders to increase awareness of IPAWS; that FEMA work with subject-matter experts to develop training, testing and credentialing of alert originators; and that the agency establish 24/7 online and phone support.

That first recommendation — working with additional stakeholders — is a key one, said Digital Alert Systems Senior Director of Strategy & Regulatory Affairs Ed Czarnecki, who served on the iPAWS subcommittee that drafted the final report.

“In terms of prioritizing what FEMA could look at in the near term (12 to 24 months), FEMA would be well served to expand its engagement with the broad range of stakeholders involved in alert and warning systems,” Czarnecki said. The goal is to “build that critical feedback loop between IPAWS and the diverse array of technology developers, alert originators and disseminators like broadcast and cable,” he said.

BUILDING AWARENESS

The report also emphasized the importance of beefing up public knowledge of the IPAWS system. As part of “Improving public and congressional understanding of emergency alerting,” this education includes briefing the public on the difference between official IPAWS alerts and other types of alerts.

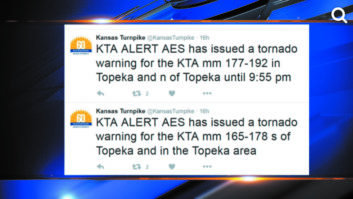

Why is this significant? Take one case in 2016 when the Kansas Turnpike Authority, a privately owned roadway operator, sent out tornado warning alerts to their nearly 12,000 subscribers. According to the National Weather Service, there was no tornado warning.

Since there were no official government warnings, the situation caused public considerable public confusion. The local chief meteorologist on KSNT(TV) went on air soon after to reassure those in the area that there was no sign of an impending tornado on radar.

“Currently, it is not easy for the public to recognize the difference between an IPAWS-distributed and private sector-distributed alert,” the report authors said. “Several private sector-distributed alerts have confused the public and eroded confidence in — and compliance with — alert guidance.”

The report also proposed that FEMA educate lawmakers about needed improvements to the nation’s emergency alerting systems by, among other things, clarifying the need for multiple and redundant alerting technologies and encouraging the use of public media broadcast capabilities to fill gaps in rural and underserved areas.

COMMON PRIORITIES

There are a number of priorities that pop up across all 14 proposed themes. One of those is that it’s vital for the alerting community to establish a series of best practice procedures across all levels of the emergency alerting strata. Another is that there needs to be an additional effort placed on educating the public about alerting and how individuals should respond in case of an emergency.

For example, the top recommendation under the theme “Optimizing technology” is that FEMA must lead the development of a comprehensive standard set of communication tools — be they visual images, pictograms, transcripts or captioning — so that populations can easily understand an alert.

This is even more important as populations become increasingly diverse; it’s paramount that IPAWS ensures that people with disabilities and those with limited English proficiency receive and comprehend alerts in a timely manner, the report said. It noted that uneven distribution of alerts in various languages was an issue during the 2018 Northern California wildfires.

“Local agencies, which originate most alerts, vary widely in their capacity to generate alerts in languages other than English,” said California’s Office of Emergency Services in the wake of the wildfire that destroyed 18,000 structures and killed 86 people. “In many cases, this capability varies depending on which language-skilled staff happens to be on duty when an alert is required.”

The report proposed, as an example, that FEMA develop a nationwide, standardized hazard symbol set for use by alert originators and for public outreach.

[Xperi Seeks Bigger Role in Alerting]

The report also proposed that FEMA develop a policy for redundant alert origination as noted in the section “Identifying and Adopting Current and Future Technologies.”

“Considering that a jurisdiction’s primary alerting capability can be compromised and/or fail during a catastrophic event, alternate alert origination is a critical life-saving capability,” the report said. It cited the malfunctioning of part of the alert system in Texas during Hurricane Harvey and damage caused to the communications infrastructure in the Caribbean islands during Hurricane Maria. In the latter case, emergency management officials were unable to issue a WEA alert to notify residents of where to find shelter, food and water.

The report also includes details on considerations such as staffing needs and equipment requirements. The complete version can be found at www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/177192.