This is the story of a station whose transmitter for two decades sat on an island — arguably the most famous such “island station,” WCBS 880.

The non-directional 50,000 watt powerhouse station, now owned by Audacy (the former Entercom), has been doing the demanding 24/7 format of news, sports and information for more than 50 years. At times it has been the nation’s most listened to station.

How did its transmitter end up on an island?

The saga of this flagship of the Columbia Broadcasting System started with the cigar business of Samuel Paley in the early 1920s. He owned a distribution company at a time when one of America’s growing male vices was a good cigar — or multiple cigars — a day. He dealt mainly with imports and focused on building brand recognition and brand loyalty to succeed in this emerging business.

Radio was “trending” at the time, the “new big thing.” Ad placement was the bailiwick of Sam’s son William Paley; they started using radio — ads and mentions — to get cigars into as many mouths as possible.

The power and the cost-effectiveness of radio piqued the younger Paley’s interest. Shortly thereafter the CBS epic began when he took over management of a nascent network of 16 stations, the Columbia Phonographic Broadcasting System.

In short order the Paley family and partners bought the operation. With 51 percent ownership, he ran and now controlled the network.

The file on WCBS starts with a different set of call letters. In 1924 the Atlantic Broadcasting Company applied for a New York station and got the apropos call of WABC. As with many stations of this period, WABC meandered around the dial until in 1932 it wound up on 860 kHz with 50 kW non-directional and a transmitter in Wayne, N.J.

The population of metropolitan New York was expanding along roads and transportation lanes into Brooklyn, via the famous bridge, and New Jersey, via the Holland Tunnel. Those demographic trends and travel corridors influenced the choice of new transmitter sites. Managers of other early stations serving New York City such as WOR and WEAF did likewise.

Central location

In 1936, CBS purchased the signal, adding to its station portfolio and distribution network.

In 1940 it sought to move the transmitter from New Jersey to what was then called Little Pea Island, located in lower Long Island Sound and northeast of Manhattan.

CBS bought the island and installed an aux transmitter for testing. The results demonstrated that the seawater conductivity would ensure formidable coverage in New York and New Jersey, and bonus extensive penetration into populous sections of Connecticut.

With the 1941 North American Regional Broadcasting Agreement, the station moved from 860 to 880 kHz shortly before the final move.

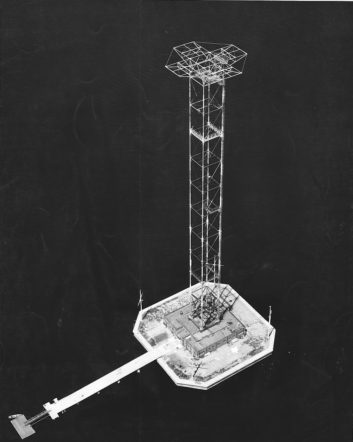

Little Pea Island — later renamed Columbia Island — is a modest tidal rock of about one acre in size. It became home to an extraordinary engineering installation featuring a 410-foot self-supporting top-loaded tower. In 1941 two underwater cables brought power from New Rochelle to the site, and operations began.

News accounts said CBS spent approximately $500,000 (the equivalent of about $9 million now) to construct the tower, transmitter with backup and the building, including emergency housing for 10 workers.

A headline in the New York Times in October 1941 read: “Radio ‘Island’ Comes to Life; WABC’s New Transmitter Is Called an Engineering Dream — Built on a Man-Made Rock in Long Island Sound.”

Daily boat runs brought a change of operating crew, food, potable water and other creature comforts from the “mainland.” Weather and waves were not always cooperative. The bedrooms, kitchen and other quarters were put to use by stranded crews when circumstances isolated the site.

Federal Radio, a division of IT&T, built the transmitter from its own advanced design. Few details for this rig are available but Federal used it as a model for CBS’s later shortwave station further out Long Island.

Evidently this earlier, similar 50 kW unit was plate modulated. The high voltage supply took three-phase power direct from the power company at 4600 volts using banks of mercury vapor rectifier tubes to make DC. Filaments were transformer-powered unlike earlier motor generator schemes.

Jim Weldon of border blaster fame worked on the Columbia Island station as a Federal Radio engineer.

The official starting date was Oct. 18, 1941, with Kate Smith and Orson Welles, personalities well connected with CBS, participating in the inauguration.

In 1946 the company received approval to change the station call letters from WABC to WCBS.

Up until the late 1950s transmitters were operated on site by engineers who were on duty whenever the station was on air.

The station had a tremendous signal penetration and was the very definition of a “clear-channel, Class A station” that reached well into the heartland of America. Further, the saltwater location provided possibly an even bigger reach throughout the Atlantic, making it the voice of New York City to many far away at sea in war and the following peace.

Like other similar important big stations including WTIC and WCCO, WCBS during World War II had a guard detail to protect the facility from sabotage or disruption.

One story, legendary but probably true, is that in thick fog, the crew once found its way to the island by following the induction field created by the currents flowing in the underwater power cable.

Moving on

Columbia Island provided a superb signal for CBS, but this rock was an expensive site to operate under any definition.

With the emergence of TV and the dropoff in network radio revenues, CBS explored locations nearby that were easier and more convenient to reach.

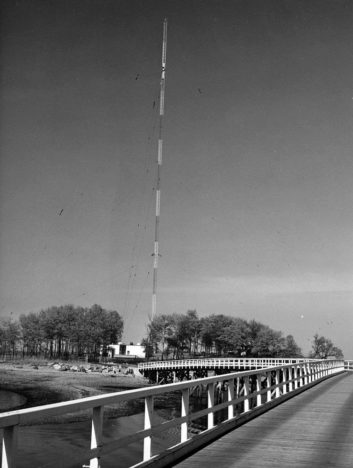

Eventually the corporate engineers settled on High Island just off the Bronx shore as a more practical site with a desirable land connection via a sandbar bridge.

After some delay and birthing pains, WCBS moved to that site in early 1962, where it remains today.

WNBC, 660, was diplexed into the tower shortly thereafter when crooner Perry Como decided he wanted the nearby site that NBC was developing for his New York City home! WNBC is now sister station WFAN 660. (It was this site that was knocked off the air by the fatal crash of a private airplane in 1967 on the day before WCBS launched its all-news format.)

Meanwhile, according to news accounts, Columbia Island was purchased by a show-business couple who aired a breakfast conversation show from their home there; then it went through multiple hands including the College of New Rochelle.

Actor Al Sutton eventually acquired it and built a “green” home on the site; you can find online stories about its construction, which is interesting in itself. At this writing, Zillow listed it for sale at $13 million. You can even take a video tour online.

But regrettably the 20-foot-square, 410-foot-high tower is long gone — regrettable, because for any resident the radio reception using that stick would have been extraordinary.

Broadcasting has often found some advantage or necessity to locate transmitter sites on islands. These islands vary from the isolated home of KUHB on frigid St. Paul Island in the Bering Sea to the defunct directional AM of WRIZ built on an island of pilings in Biscayne Bay in Florida.

If interested, we’ll visit some other islands in the stream in future columns. Please let us know your favorite or most engaging island station. Email radioworld@futurenet.com.

Charles S. Fitch, P.E., is a longtime contributor whose articles about engineering and radio history are a popular recurring feature in Radio World.