For nearly 30 years, audio tape carts were essential to radio station operation, first for spots and later for music. Their initial development is a fascinating story with many loops, er, twists and turns.

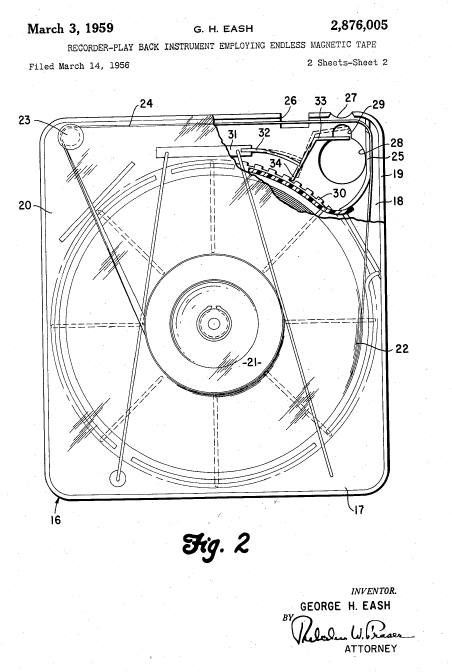

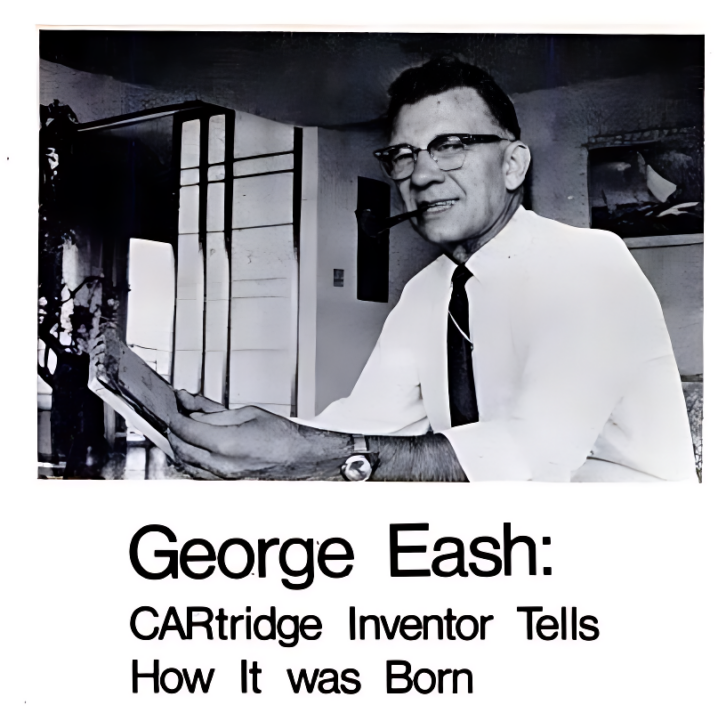

In the early 1950s, George Eash of Toledo, Ohio, experimented with loops of tape in a bin and a device to apply graphite to the back of the tape to lubricate it as the tape slid on itself during playback.

He was granted several patents for his inventions and initially was dismissive of new back-lubricated tape from Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing and Reeves-Soundcraft. However he quickly changed his mind.

His patent for a cart shell to hold the tape loop would become the standard. A Chicago company was licensed to manufacture the cartridges using the Fidelipac name. Several manufacturing companies followed.

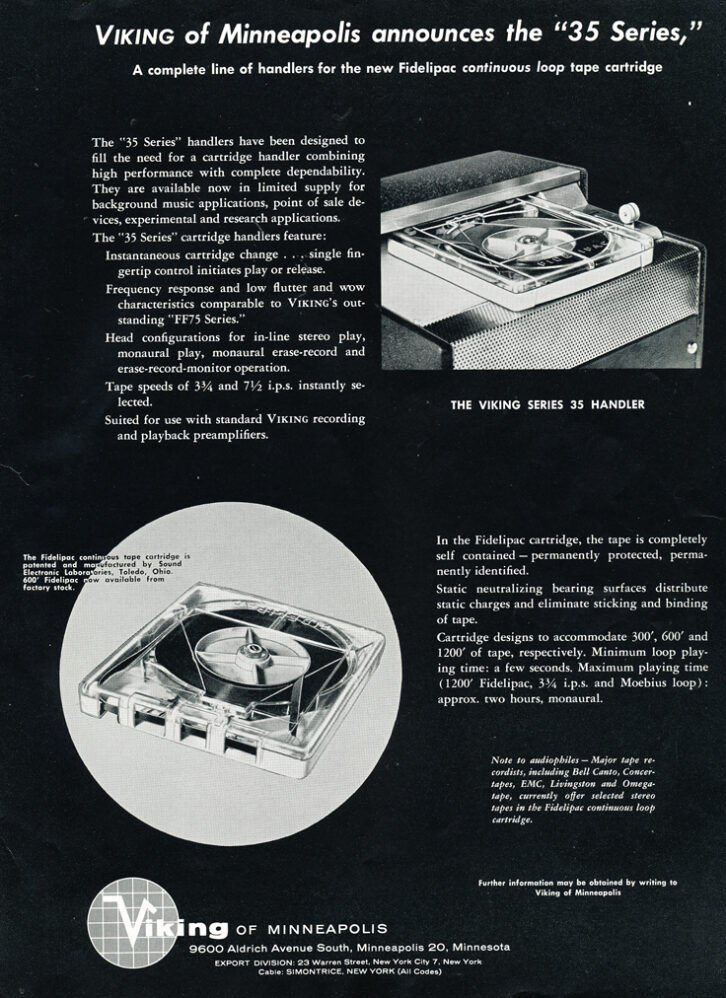

Eash worked with the Viking metal stamping company in Minneapolis to build a transport deck matching his design in a 1956 patent application. Viking improved on Eash’s pressure roller mechanism in its model 35 in 1957. The deck could operate at 3-3/4 or 7-1/2 inches per second. Several head configurations could be used, including mono and stereo. The cost was $70.

In the background

Originally, tape cartridges were designed for background music and retail point-of-sale displays, which is the application that Moulic Specialties — eventually known as SMC — began modifying Viking decks for in the late 1950s. The electronics manufacturing company, located in Bloomington, Ill., was started in 1945 by local electrical engineer, instructor and author William Moulic.

One of Eash’s patents had mentioned possible use in broadcasting, which is exactly what the general manager of WJBC in Bloomington thought when he saw Moulic’s decks in action. Vern Nolte tasked station engineers Ted Bailey and Jack Jenkins with modifying the decks for broadcast use, initially only by WJBC.

They developed prototypes using a two-track machine, with one track for mono audio and the other for cueing. They added a 1 kHz tone generator and sensor to provide automatic tape re-cue and a solenoid to the Viking decks for a faster start. Prototypes were shown at the Illinois Broadcasters Association meeting in October 1958.

WJBC created a company named Automated Tape Control (ATC), but it had no marketing, manufacturing or sales capability. Nolte proposed that Gates Radio in Quincy, Ill., handle these aspects, but Parker Gates declined, saying he was working on a spot playback deck of his own called the ST-101.

After its district rep Gene Randolph saw the machines in a sales call at WJBC, the Collins Radio Company asked to market the devices. Their introduction was made at the 1959 NAB Show. Moulic Specialties assembled the machines using Viking decks, ATC built the modular tube electronics and Collins built the cases and displayed the decks.

Despite the decks almost self-destructing by overheating in the Collins’ cases, they became a hit of the show, reportedly generating more than $100,000 in sales to 45 radio stations, roughly equivalent to over a million dollars today.

On the Spot

Around the same time, Chief Engineer Ross Beville at WWDC in Silver Spring, Md., modified a Viking transport and displayed it at a fall 1958 audio show in the Washington area. Beville was surprised to see the ATC gear at the 1959 NAB Show because he was just two months from receiving a charter for his new company, Broadcast Electronics, to manufacture and market a line of cart decks called Spotmasters.

Spotmasters first used the Viking model 35 transport. A pinch roller solenoid was added for fast starting and a half-track head was used for primary tone generation and detection for automatic cuing. After producing a number of these modified decks, Viking agreed to add a solenoid to their standard deck design.

Wanting other design changes to make the deck more rugged under constant usage, BE disassembled every finished Viking transport and replaced various components. Viking eventually agreed to produce a ruggedized version of the deck exclusively for Broadcast Electronics.

The Spotmaster used an 850 Hz primary tone rather than ATC’s 1,000 Hz, and a 150 Hz secondary rather than ATC’s 3,200 Hz. Both BE and ATC soon standardized on a 1,000 Hz primary and a 150 Hz secondary, with BE adopting these after producing about 50 units.

Randolph at Collins said he grew tired of hauling the heavy ATC record and playback units into radio stations for demonstrations, so he installed decks into the folding backseat footrests of a used Cadillac limousine. Several TV stations featured the setup, and Randolph said it paid for itself within the first six weeks.

Despite the initial NAB Show sales and Randolph’s success in his own sales territory, adoption by very large stations and networks was much slower than in small markets. Bailey recalled meeting with engineers at WIL in St. Louis in 1959. One union member said, “If it’s new, I’m against it.” Bailey noted that announcers could place a cart in the machine, but engineers had to press the remote start button.

By 1961, ATC had developed its own manufacturing facilities in Bloomington.

Automation

Aside from the slow adoption by stations, poor audio performance due to manufacturing and station maintenance issues became a problem.

In 1963, one of the nation’s major advertising agencies, J. Walter Thompson, forcefully requested that non-automated stations play spots from disks rather than carts because of poor spot audio playback quality. Ted Bailey recalled two early ATC machines taken in on trade, one labeled Pokey and the other Speedy.

In 1966, Gates purchased ATC following its unsuccessful ST-101 production and moved ATC’s operations to Quincy. Some employees stayed in Bloomington and formed a new company called International Tapetronics Corp. or ITC. Meanwhile BE outgrew its radio station location and relocated to a larger Silver Spring facility, then to Rockville, Md. and finally to Quincy, Ill. (as recounted in a recent Radio World article about businessman Larry Cervon).

Program automation became more popular with the FCC’s 1964 requirement to separate AM and FM programming and to control costs. Machines to automatically sequence and play multiple tape cartridges were developed including the ATC 55 and SMC Carousel.

Rather than slowly declining as BE had forecast, new cart machine sales plummeted in the late 1980s. The consolidation of radio stations into centralized studio complexes, made possible by the loosening of FCC ownership regulations, made managing duplicate cartridges for each station’s spots unwieldy in larger markets. Even with multiple cart players, carts didn’t offer the desired walkaway time in smaller markets that had begun using long-form satellite-delivered programming. The switch to PC audio cards with controlling software seemed to happen much more quickly than the adoption of tape cartridges had.

More info

This article builds on a paper by Dr. David MacFarland, “Archaeology of the Broadcast Tape Cartridge,” as well as tape cartridge machine history by Andy Rector, formerly of ATC, ITC and Audi-Cord, for a 2009 manufacturers’ reunion. See the latter on the SBE Chapter 24 site.

More detailed information about the development of cart technology, including biographical of those involved, is available in a series of Facebook posts by the page Radio History.

- Fidelipac: https://tinyurl.com/yu3r46ma

- SMC: https://tinyurl.com/2mjdne97

- ATC: https://tinyurl.com/25bdj4vx

- BE: https://tinyurl.com/y5h3m62a

Share your memories of cart machines. Email radioworld@futuenet.com with “Letter to the Editor” in the subject field.