Today’s country music genre had its beginnings in the 1920s with the popularization of two types of music: rural white bluegrass or “hillbilly” music and “western” or “cowboy” music.

The two styles eventually merged in the 1940s and ’50s to become “country and western” music, or what is today simply called country. Perhaps the most important catalyst in the popularization of these music styles was radio broadcasting. It’s possible that, without the influence of radio, today’s country music would not exist.

Starting in 1927, radio broadcasting became dominated by the large national networks, NBC and CBS. But the big networks wouldn’t cater to the western or hillbilly audiences. One reason was their worry about the licensing liability of music that was often of unknown origin. But it was also felt beneath their dignity to perform “uncultured” music styles. Along with Black or “race” music and “hot jazz,” rural white music was equally ignored. NBC in particular limited itself mostly to symphony and light opera music in the 1930s, and by the following decade it had cut back its musical content in favor of drama and comedy shows.

There were exceptions, like the “NBC Radio Rubes” cowboy singers of the early 1930s, but, as the group’s name itself implies, the music was presented in a belittling manner. Even radio’s popular characters like Judy Canova and Lum and Abner played unsophisticated country bumpkins, diminishing the image of rural white America.

Notwithstanding the networks’ disinterest in rural music, it was individual radio stations across the country that were responsible for bringing the various genres of country music into the mainstream of popularity. Unlike the national networks, they only had to please the audiences of their local regions. Most of these were Midwest and Southern stations that targeted rural working-class audiences.

The “Barn Dance” Shows

The earliest venues for country music were the immensely popular “barn dance” programs on several powerhouse Midwestern stations in the 1920s and ’30s. The first of these was “National Barn Dance,” which premiered on WLS in Chicago in 1924 under the direction of George D. Hay. In 1925, Hay took the concept to WSM in Nashville, which began the amazingly successful run of the “Grand Ole Opry” (1925–present).

Other important programs in this genre were the “Iowa Barn Dance Frolic” on WHO in Des Moines (1931–53); the “Renfro Barn Dance” on WLW Cincinnati (1939–57); the “KSTP Sunset Valley Barn Dance” in St. Paul MN (1940–57); and the “WWVA Jamboree” from Wheeling, W. Va. (1933–2007).

The WLS “National Barn Dance” was so popular that Paramount even made a movie about it in 1944. Many decades later, the barn dance format was revived for the popular “Prairie Home Companion” radio show.

The “Hillbilly” music genre was also promoted by hundreds of less powerful stations in smaller communities —stations like KMA in Shenandoah, Iowa, WDZ in Tuscola, Ill., KGVO Missoula, Mont., and KTRB Modesto, Calif.

Early mornings on these stations were often directed towards the farm audience, with country music interspersed with commodities reports. Weekend evenings were the best times for the jamboree-type programs, which were often broadcast through regional hookups of multiple stations: “Dixie Jamboree” was heard over WMC Memphis, Tenn., KARK Little Rock, Ark., KWKH Shreveport, La., and WSMB New Orleans; and the New England Radio Network broadcast the “Down Homers” early mornings over WBZ Boston, WCSH Portland, Maine, WJAR Providence, R.I., WLBZ Bangor, Maine, and WTIC Hartford, Conn.

Another radio boost to white rural music came from the “border blasters” — the high-powered Mexican stations that were heard across the U.S. each evening. The biggest among these was XERA in Del Rio, Texas, which famously introduced the Carter Family to American audiences.

It’s not surprising that many stations turned to hillbilly or cowboy music to attract local audiences. Of the 738 stations on the air in 1938, 437 were in cities under 100,000 population, and 246 served less than 25,000 people. An FCC study that same year showed that just 29.2% of the nation’s radio broadcasts came from the networks, compared to 30.8% featuring live local talent.

The ASCAP Music Boycott

One of the biggest boosts for the growth of country music took place in 1941. Since the first days of broadcasting, radio stations had been paying The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers a blanket annual fee of 5% of advertising revenue for the rights to perform their licensed music. But in 1940, ASCAP announced it was tripling its music fees for radio!

In September 1940, industry leaders met at the NAB convention in San Francisco and resolved that all radio stations and networks would boycott ASCAP music. On Jan. 1, 1941, more than 1 million ASCAP tunes disappeared from the airwaves.

With the support of the NAB, broadcasters organized BMI (Broadcast Music Inc.) as the industry’s own music licensing agency. BMI sought out new unknown composers who weren’t contracted to ASCAP and then released this new music to stations at a much more favorable rate. Genres that the elitist ASCAP had always considered beneath their dignity to license — Latin, “hillbilly” and “race” music — were a sizable part of this new library.

Once again, it was the individual stations that spearheaded the move to country music, as the national networks only further eliminated country music from their schedules. Since much of the music came from unidentifiable sources with unknown copyright risks, CBS, NBC and Mutual stayed away from the genre. To fill their airwaves, local broadcasters relied on BMI and public domain songs, but they also tapped into another source of music: Although the big country artists like Gene Autry were ASCAP members, dozens of little-known territorial bands were not, and they often wrote their own music, not licensed by any organization. Broadcasters were more than happy to broadcast this license-free music, and they found that the programs drew listeners and advertising dollars.

Coinciding with the radio boycott, the Department of Justice began investigating ASCAP for monopolistic practices. Finally, facing the combined pressure of broadcasters and the government, ASCAP backed down. By summer’s end it had signed an agreement for 2.75% of revenue on network broadcasts and 2.25% for local station programs — less than half of what it had been earning before 1940!

The boycott officially ended in October 1941 and America’s pop music standards returned to the airwaves. But something had changed. American listeners had been exposed to new music genres and they liked it. “Hillbilly” music gradually morphed into the more refined “western” music that was immensely popular on radio in the 1940s. “Race” music became rhythm and blues, later merging with jazz to become rock and roll. In just 10 months, radio had demonstrated its great ability to shape popular music tastes.

Indeed, it became clear that the public’s taste in music was broader than previously assumed, and varied from region to region. A survey in Texas revealed that 38% of farmers preferred “hillbilly” music. A 1948 AMC survey of 4,200 families around the country found that 54.7% appreciated old favorites and folk tunes and 37.8% liked “cowboy” and “hillbilly” music.

Even in large metropolitan cities, 33% “occasionally enjoyed hillbilly music.” Nonetheless, the 1940s saw a shifting of music styles away from “hillbilly” music in favor of “western” tunes. This change was driven by the romantic image of the old west cowboy, popularized by the Western movies of the era.

The Regional Bands

As country music grew in popularity in the 1940s, it seemed that every radio station in the country had to have its own live cowboy music program.

Hundreds of small regional bands popped up around the country, playing live shows on their local stations to promote their personal dance appearances and recordings. There were such colorful names as “The Cook Crick Boys” (KWK St. Louis and KWOS Jefferson City, Mo.); “Larry Gondringer and His Prairie Swingsters” (KHAS Hastings, Neb.); “Yodeling Johnny, the Wandering Cowboy” (KROY Sacramento, Calif.); “Radio Dot and Smokey” (KWKH Shreveport, La.); “The Cumberland Ridge Runners” (WLS Chicago); The “Mountaineerfuls” (WRRC Clinton, N.C.); and the “Dude Ranch Buckaroos” (WFAA Dallas). There were all-girl bands like “The Saddle Sweethearts” (WNAR Norristown, Pa.); “The Montana Sweethearts” (WDZ Tuscola, Ill.); and “The Texas Bluebonnets” (KMOX St. Louis).

Bands often migrated from one station to another to find better booking opportunities. Some bands had regular gigs on stations in different cities, sometimes using a different name in each city. And many bands traveled the country, playing shows and county fairs, also performing on local stations as they passed through.

Sponsors found these local radio shows were a good way to target rural audiences, and they underwrote programs on a number of stations. Crazy Water Crystals, a laxative product from Mineral Wells, Texas, specialized in advertising “hillbilly” programs on stations like WBT in Charlotte, N.C., and XERA in Del Rio, Texas, starting in 1934.

Peruna Tonic, a patent medicine sold until the mid-1940s, sponsored programs on WLS (“The Cotton Queen Program”) and KMOX (“The Peruna Ozark Mountaineers”). Other bands took the names of their radio sponsors, such as “The Lightcrust Doughboys” (KPRC Houston) and “The Argotane Entertainers” (WMC Cedar Rapids, Iowa).

In some cases, it was the radio stations themselves who helped promote the live appearances of their local bands, generating income for both the stations and musicians. WDZ in Tuscola, Ill., formed an artist’s bureau with booking agents to promote their bands’ live shows. The station even had a portable tent that it set up for shows in different cities within its coverage area.

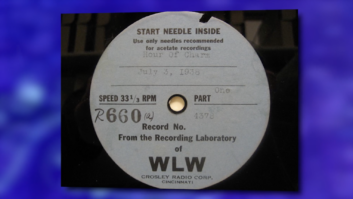

As the disc jockey format began to take shape in the 1940s, these bands cross-promoted themselves in distant cities by sending their records to the deejays. KTBS in Shreveport broadcast its “Cowboy Jamboree” every night at 11 p.m., and all of the records played were either donated by bands or audience members. WNOE in New Orleans had the “Jukebox Jamboree,” and WJJD in Chicago featured Randy Blake, the “Hillbilly Deejay.” These DJ programs moved into the mainstream as radio adapted to the television age in the 1950s, although live cowboy band broadcasts were still quite popular.

The first all-country station appeared in 1953, KDAV, Lubbock, Texas. This set the stage for the single-formatted C&W stations of the 1960s, moving into the FM band in the 1970s. Today, there are more country music stations in the United States than any other format (an estimated 2,100 stations), and country music popularity is at an all-time high. The radio industry is riding a huge wave of commercial success that was, in great part, of its own creation.