This is part of a Radio World series to celebrate early broadcasters as the industry prepares to note the 100th anniversary of what is, traditionally, considered the birth of modern commercial radio. This article was prepared with special assistance from Jim Hilliker.

This is part of a Radio World series to celebrate early broadcasters as the industry prepares to note the 100th anniversary of what is, traditionally, considered the birth of modern commercial radio. This article was prepared with special assistance from Jim Hilliker.

In 1920, Fred Christian left his employment as a Marconi shipboard radio operator to become the manager of the Electric Lighting Supply Co. in Los Angeles. In addition to selling lighting fixtures, he began to offer the radio parts that tinkerers needed to build their own homemade radio sets.

From a back bedroom of his home, Christian also operated his 5 W amateur radio station, 6ADZ. On or about Sept. 10, 1920, he began broadcasting phonograph records borrowed from a local record store. Music transmission was not prohibited by amateur operators at that time, and dozens of hams around the country were broadcasting on informal schedules.

Christian, operating at the bottom of the ham bands on 200 meters (1500 kHz), was only the second radio station to broadcast in Los Angeles to that time. His aim was to promote the sale of radio parts in his store by giving his customers something to listen to.

The California Theatre

In 1920, there were still no fixed regulations governing broadcasting, and the first stations operated under a variety of license classes, such as amateur, experimental or “commercial land station.” (The renowned pioneer station KDKA debuted with a new category called “limited commercial” license under the call sign 8ZZ.)

But starting in December 1921, the Department of Commerce required all stations broadcasting news or entertainment to hold a “Limited Commercial” license, and so most of the handful of stations already broadcasting by that date obtained new licenses with new call signs.

By March of 1922, there were 66 such licenses issued. Regrettably, they were all required to transmit their programs on one of just two frequencies: 360 meters (833 kHz) for entertainment, or 485 meters (619 kHz) for market and weather reports.

Thus, Christian’s station 6ADZ acquired the call sign KGC, and it was now sharing a single frequency with about eight other broadcasters in the Los Angeles Basin. Those stations met periodically to agree on a shared operating schedule, and KGC was only able to operate a few hours a week.

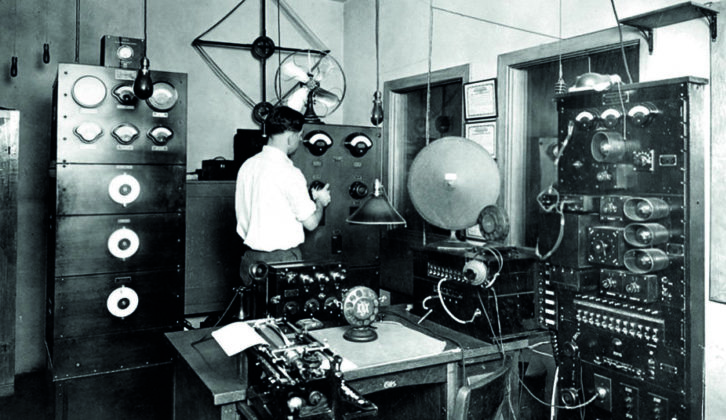

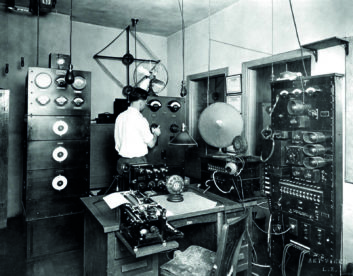

In May of 1922, Christian made arrangements to broadcast live music from the California Theatre, a prominent silent movie house. He built a new 50 W transmitter (soon increased to 100 watts), and moved his entire operation into the theatre. The move necessitated a change in operating license, and he was assigned the new call sign, KNX, with the old KGC license being deleted shortly afterwards.

Christian’s was one of several stations that changed licenses that year, considered by the government then to simply be the transfer of a station from one license class to the other without an interruption in service. Both licenses were in the name of the Electric Lighting Supply Co., and Fred Christian was listed as the station manager and operator in both instances.

Calling itself “The California Theatre Radiophone,” KNX was now broadcasting live music four or five days a week, featuring Carli Elinor’s California Theatre Concert Orchestra and the music of the theatre’s organ. A nightly newscast was also featured.

But finances to support the station were limited; advertising was not yet condoned on broadcast stations, and so the entire operation was being supported by the sale of radio parts at the store.

“The Voice of Hollywood”

In October 1924, Christian sold KNX to Guy C. Earle, publisher of the Los Angeles Evening Express newspaper, who had the means to turn it into a first-class operation. Starting in 1923, stations that agreed to transmit with at least 500 watts and abstain from playing recordings were eligible for the new Class “B” license and their own dedicated frequency, so Earle bought a new Western Electric transmitter and moved KNX to 890 kHz.

KNX was now “The Voice of Hollywood” — on the air from morning to late night with sports, news, informational talks, drama by the “KNX Players” and live evening broadcasts by Abe Lyman’s Orchestra from the Hotel Ambassador.

Earle hired Carrie Preston Rittimeister to be his program director. She had experimented with paid programs at another Los Angeles station, and soon had KNX on a paying basis five nights each week.

The sponsors were local companies seeking name recognition, and there was a minimum of direct advertising in the programs themselves. By 1925, KNX was showing an operating profit of $25,000.

In 1929, Earle signed a five-year contract with Paramount Pictures, moving the KNX studios onto the Paramount movie lot. KNX was now the “Paramount-Express” station. Taking advantage of its Paramount connections, KNX became the first station to broadcast the Academy Awards in 1930.

In 1929, KNX was awarded 1050 kHz, one of two new clear channels the Federal Radio Commission had assigned to Southern California. A new 5,000 W transmitter plant was erected in Sherman Oaks in the San Fernando Valley, and a star-studded 24-hour dedicatory program was planned for Nov. 11, at which time KNX would debut its new powerful signal for the first time.

When the dramatic moment came to switch over to the new transmitter, radio listeners heard only a tremendous screech on the new frequency, and then … silence! After a few moments, the old 1 kW transmitter was coaxed back onto the air.

It was several days before the engineers could sort out the problem and settle KNX into its new channel. Then they discovered another problem: The new 5,000 W signal was not being reaching out as well as the old signal.

Consulting engineers were brought in from across the country to puzzle over the case, and they eventually determined that the fault was in the antenna, a 179-foot wire cage suspended between two 250-foot supporting towers. The towers were resonating at the 1050 frequency, disrupting coverage. The problem was ultimately solved by inserting porcelain insulators at the base of the towers.

Guy Earle soon sold his interests in the Evening Express newspaper and devoted all of his energies to KNX, now operating as the Western Broadcasting Co. One of California’s renowned engineers, Kenneth Ormiston, went to work planning to increase power on the clear channel frequency — to 10,000 watts in 1932, to 25,000 in 1933 and finally to 50,000 watts in 1934. In all cases, the 1929 Western Electric 5,000-watt transmitter was used as a driver for the high-powered amplifiers built by Ormiston.

After WLW in Cincinnati was allowed to operate experimentally at 500 kW, plans were drawn up for a further increase to 250 kW, but the idea was abandoned in favor of a new half-wave self-supporting tower, constructed in 1935, which greatly increased signal strength at a fraction of the cost of a huge transmitter.

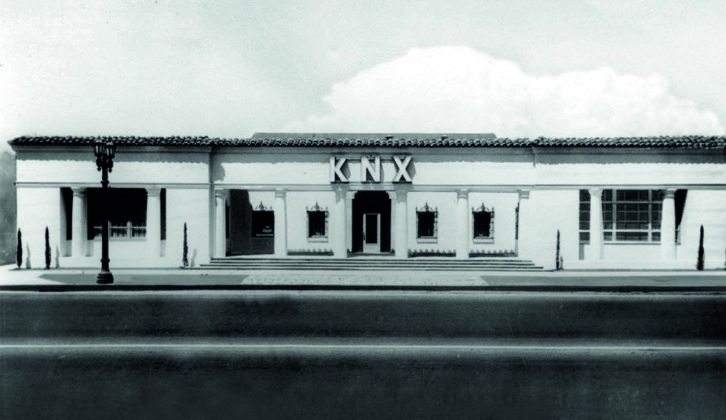

In 1935, Guy Earle bought the 20,000 square foot Motion Picture Hall of Fame building at 5939 Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, and rebuilt it into the new KNX studio building at a cost of $250,000. It featured six studios suspended on floating floors. Studio “A” was 30 x 60 feet, and Studio “B” featured a new $35,000 Morton organ. Brand new RCA studio equipment was installed throughout.

Enter CBS

KNX was now a powerhouse station, with a powerful signal covering eleven Western states a night. It’s 1935 gross income of $675,000 ranked it among the six highest-billing stations in the country.

But the FCC became aware that much of that revenue was coming from the advertising of patent medicines, which the commission was seeking to eliminate from the airwaves. It decided to make KNX into a test case, and it set its license renewal for hearing over its advertisement of Marmola, a miracle fat-reducing product that the Federal Trade Commission determined to be ineffective and dangerous.

The hearing in October 1935 did not go well, and the KNX license was now in serious jeopardy.

In 1936, under pressure over the license hearings, Earle sold KNX to the CBS network for $1.25 million. It was the highest price ever paid for a single radio station to that date.

KNX was now CBS’s key station on the West Coast, and would soon become the home base for CBS’s Hollywood program origination.

In January 1937, CBS moved its Los Angeles network affiliation to KNX from KHJ and the Don Lee network, which caused a major realignment of network affiliations up and down the West Coast. Then on April 30, 1938, KNX and CBS moved into its new $1.75 million Columbia Square studio complex at 6121 Sunset Boulevard.

It would be the origination location for dozens of CBS radio shows heard nationwide over the next decade, featuring stars such as Jack Benny, Bing Crosby, Burns and Allen. (KMPC then moved into the former KNX Sunset Boulevard building.)

In September, 1938, CBS debuted a new KNX transmitter complex on a five-acre parcel in Torrance. A gleaming new RCA 50-D transmitter was showcased in a streamlined domed building that was open to the public for regular tours. A new 500-foot guyed tower propelled the KNX signal across all of the Western states in the evening hours. In March 1941, KNX moved to its present frequency of 1070 kHz after the nationwide NARBA treaty adjustment.

As network radio transitioned to the disc jockey era of the 1950s, KNX adopted a middle-of-the-road format, featuring personalities like Steve Allen and Bob Crane, who broadcast his popular KNX morning show from 1957 to 1965 before leaving to become the star of the TV series “Hogan’s Heroes.”

In September 1965, vandals cut a guy wire, destroying the KNX tower. The station operated from a 365-foot unused tower acquired from KFAC until a new antenna could be built. An experiment using both antennas as a directional array during the 1960s was abandoned, but both towers still exist today.

The 365-foot tower is now the KNX standby antenna, located inside a city park in Torrance.

In April 1968, KNX adopted an all-news format, which has successfully maintained it as one of the top ten news stations in the country. Entercom Communications acquired KNX in 2017 when it merged with CBS Radio. KNX will celebrate its 100th anniversary on Sept. 10, 2020.

John Schneider is a lifetime radio historian, author of two books and dozens of articles on the subject, and a Fellow of the California Historical Radio Society. He wrote here in April about Lee De Forest, and last winter about the centennial of KRJ, perhaps the first in the U.S. to achieve a century of continuous broadcast activity.

References & Further Reading

• KNX History, by Jim Hilliker

• Email from Jim Hilliker, 2/27/2020

• “Broadcasting Magazine,” 10/1/35, 3/1/35, 2/1/35,

• “Radio Digest,” October, 1924; November, 1924; May, 1925

• “Radio News,” March 1930

• “Department of Commerce, Radio Service Bulletin,” 6-30-21, 5-1-22, 6-1-22

• “Radio’s Version of ‘Who’s on First?’” by Jeff Miller

• “Los Angeles Times,” 6-12-22

• KNX AM, Wikipedia

View the images above at full resolution: