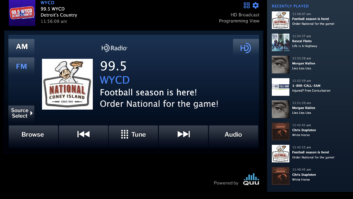

Fig. 1: Know who owns your site — and let them move the boulder. Taking care of a new transmitter site? After you survey the equipment, also find out who owns the property and write down the contact info.

Here’s an example of why that’s a good idea.

Contract engineer Ron Gnadinger tried to access a site recently only to be denied by this rock in Fig. 1.

Where the boulder came from is anyone’s guess, but it wasn’t the tenant’s responsibility to remove it.

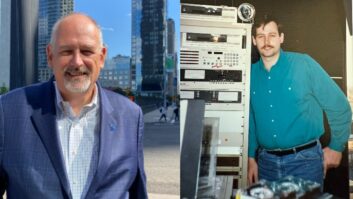

Ron started in broadcasting back in 1987 and now does contract work for a handful of stations in Michigan. His credo has been to find problems before they become serious and cause long off-air outages.

He spotted the boulder during a routine maintenance session. By making that discovery and then by notifying the property owner, he solved a problem that otherwise could have turned into a disaster during an emergency.

By the way, Ron’s contribution qualifies for SBE recertification credit. You can benefit by sharing your tips too. Why not e-mail me your ideas, along with high-resolution pictures, and earn some SBE recertification credit yourself?

Ron always travels with his camera; he finds a picture truly is worth a thousand words. In fact, a digital camera came in first place a year or so back when we queried readers to name the most valuable piece of equipment for a contract engineer.

Fig. 2: No, this isn’t a new method of ventilation. He adds: Make sure your camera has batteries or is charged.

In addition to explaining findings to a manager or owner, pictures can document vandalism or insurance claims and speed up processing. If lightning takes down a transmitter, take a few photos before you begin work to get back on the air. They can be precious when you are filing a claim.

* * *

Tom Taggart is CE for WRRR(FM) in St. Mary’s, W.Va. Recently, a raccoon taught him and a colleague a valuable lesson: After you’ve entered transmitters hundreds of times, it’s easy to forget to check that the power is off. After all, you’re just going to peek inside for a moment.

In Tom’s case, the station has three-phase power for their combined studio-transmitter operation. They use a Harris 10K as the main transmitter with a Harris 2.5K as the backup. For the occasional power outage, a 20 kW generator runs both the studio and the 2.5K through a sub-panel.

Early one morning, the raccoon decided to climb a power pole feeding the site and got across one leg of the three-phase. When Tom arrived, the studio was running on the generator but the 10K was still on the air, albeit around 3,000 Watts. (The blower is on one phase, the control ladder on the second phase and the third phase was the dead leg.)

Tom switched to the backup transmitter. While waiting for the power company, he figured it would be a good time to inspect the 10K.

A three-pole spring-loaded knife switch is the main disconnect for the 208 Volt feeds. There is another disconnect switch for the transmitter’s 110 circuit.

Fig. 3: Drinking and hunting don’t mix … Tom threw both disconnect switches while Bob Eddy pulled the back off the transmitter. Bob grabbed the shorting stick and tapped the capacitors, then the incoming 208 Volt terminals.

Ka-pow! Apparently the three-phase disconnect switch didn’t completely open the remaining active phases.

No damage to the transmitter; they just needed to replace a couple of big cartridge fuses and reset the breaker on the main panel.

This is a rather conventional disconnect switch, installed in 1988 along with the transmitter. In the “up” position, three knife-blade switches keep the circuit closed. Pull the handle down, and a spring is supposed to disconnect the three ganged busses.

Bob Eddy commented that he usually checks each leg with a DVM.

Either way, don’t assume. Check the voltage twice — and avoid ending up like the raccoon!

* * *

Having recently retired as a chief engineer, Phil Joiner is now with RF Specialties of Pennsylvania, running its Philadelphia office.

Like many, Phil had been a customer of the late Harry Larkin, who held that post until he passed away. Phil will be the first to admit he’s got some mighty big shoes to fill. But like Harry, he understands engineers want service.

Fig. 4: … and neither do transmitter sites and joyrides in log skidders. A case in point is bringing to Workbench readers’ attention the custom jacket color options on Cellflex A Series 7/8-inch and 1-5/8-inch foam coaxial cable. A light blue or a light gray is available, with the same UV rating as the black jacket. These often are used on water towers.

If you are looking for a means of hiding your STL or RPU line runs, drop Phil a line and ask for a PDF data sheet.

* * *

Tom Atkins is the vice president of engineering for Backyard Broadcasting and a frequent Workbench contributor.

Seeing the building lightning damage we showed in a recent issue, Tom wanted to share what a few drunken hunters did to one of his sites. They apparently decided to hot-wire a log skidder truck and go for a joyride.

Tom didn’t say; but after looking at Figs. 2, 3 and 4, I hope these guys got caught and did some serious jail time as well as having to pay for the damage.

His photos remind me of an incident related by Kindred Communications DOE Cameron Smith. In Cameron’s case, a ground system was vandalized. Cameron said the FBI was invaluable in bringing the perpetrators to justice.

Because broadcast stations operate under a federal license, vandalism or damage to their facilities elevates the incident to a federal offense. Add to that the station’s responsibility of relaying emergency messages, and Homeland Security can get involved, too.

John Bisset has worked as a chief engineer and contract engineer for 39 years. He now is international sales manager for Europe and Southern Africa at Nautel. He is a past recipient of the SBE’s Educator of the Year Award. Reach him atjohnbisset@myfairpoint.net. Faxed submissions can be sent to (603) 472-4944.

Submissions for this column are encouraged and qualify for SBE recertification credit.