Some of my earliest childhood memories are of car trips that we took, usually at night, between our home in the Texas panhandle and Dallas, where my older sister and later my brother lived. And I remember seeing those vertical stacks of red lights, some of which were flashing, and wondering what they were. “Those are radio towers,” or something to that effect, was my dad’s response.

Of course, at the time, I had no idea what radio towers even were or why they had to be adorned by those red flashing lights, but I thought they were pretty cool. Then, when I started at my first job in radio, there was a whole array of towers with flashing red lights right outside the back door. At that job, I had no responsibility for those lights, but I did know what they were for and if my job were at a non-directional station, what my responsibilities for them would be as a Third-Class Radiotelephone Operator licensee (with Broadcast Endorsement, of course).

That first radio gig was pretty much a summer job, and I landed a job at an FM station across town when it was done. That FM was located at the base of an 800-foot tower, and I worked 4 p.m. to midnight six days a week, which meant that I had to make the daily visual observation of the tower lights and faithfully enter into the operating log, “Tower lights are on and flashing.”

It was kind of a cool thing, standing in the dark at the base of that tower, listening to the ever-present Texas wind howling through the angle iron and guy wires and looking up at those red lights. The top beacon illuminated the “crow’s nest” above the top plate and beacon, and the tower had enough cross section that I could really see it and wonder what it was (I later climbed up there and saw it, the huge Huey & Phillips beacon and side marker fixtures up close).

A MYSTERIOUS BOX

The station signed off at midnight — there were few people out of bed after midnight in Amarillo, Texas, in those days, and of those that were, few had FM radios.

When the filaments and all the blowers shut off, I could hear a rhythmic grinding noise coming from the back wall. There was a mysterious electrical box of some sort that contained a motor, a cam and a pair of black bulbs with wires coming out of them. Up and down those bulbs went, one coming down as the other went up. I had discovered the tower light controls and mechanical flasher unit.

For decades after that, I found similar setups at tower sites all over. Even when we bought new towers in the 1990s, tower lights and tower light controls were very much the same. They used the same pairs of 620-watt bulbs in the beacons, the same 110-watt lamps in the markers; and they used some kind of mechanical device to produce the flash, although mechanical contacts were used rather than mercury switches by then.

Over those decades, tower lights were always a pain in the backside. It seemed like I could never keep the lights all working for long — bulbs burned out, flashers developed mechanical issues and the constant vibration on the towers would cause wiring to chafe and occasionally short out. Then when solid-state flashers entered the scene, they were prone to failure, either from lightning or overheating. We would buy them by the case.

A FLASH IN THE DARK

Somewhere back in time, we began to see strobes come into use for some towers, usually with reduced intensity at night. We had (and still have) a tower in suburban Chicago that is 450 feet high and free-standing. It cost a fortune to paint, and we had to paint it every three or four years, so as soon as the FAA lighting standards would permit, I filed to change it from red lights and paint to a dual system with medium intensity white strobes during the day and red lights at night. While we no longer had to paint the tower after that change, those tower lights were a chore to keep working. It was always something with that high-voltage gas-tube system.

Sometime later, a few manufacturers began producing direct replacement LED red beacons and marker lights. These fixtures included integral 120-volt AC power supplies, so the existing 120-VAC wiring, power and flashers could be used with them. They weren’t cheap, but with the promise of much longer bulb life, we went down that road at a lot of sites, with mixed results. At some, we had no problems and the retrofit LED beacons and markers that we installed are still working after many years. At others, we had quite a bit of trouble and any power and bulb replacement savings was quickly consumed by repair costs.

In 2012, we built a four-tower 50 kW directional array for KBRT near Los Angeles, way up on a mountaintop with the L.A. Basin below to the west and the Inland Empire some 3,000 feet below to the east. The marking and lighting for that site were very much in question for all kinds of reasons. First was for air safety and obstruction marking. Then there was the question of light pollution — how much would the various lighting options contribute to light pollution above the skyline of the Santa Ana Mountains? And then there was the question of migratory (and other) bird attraction to the lights.

ENTER LED LIGHTING

After much study, we opted to install red LED lights on the four towers, lights with tightly-focused beams that would confine the light projection to the horizon plus or minus a few degrees. That seemed to satisfy everyone, but I had my doubts that an LED tower lighting system that operated on low DC voltage would be reliable with 50 kW of medium-wave RF present. But to my amazement, I had nothing to fear. The lights worked fine, and we have not experienced a single failure to date. Their power consumption was so low that I was able to run the tower lights off solar panels and deep-cycle marine batteries for a couple of months after the towers went up but before we had commercial power at the site.

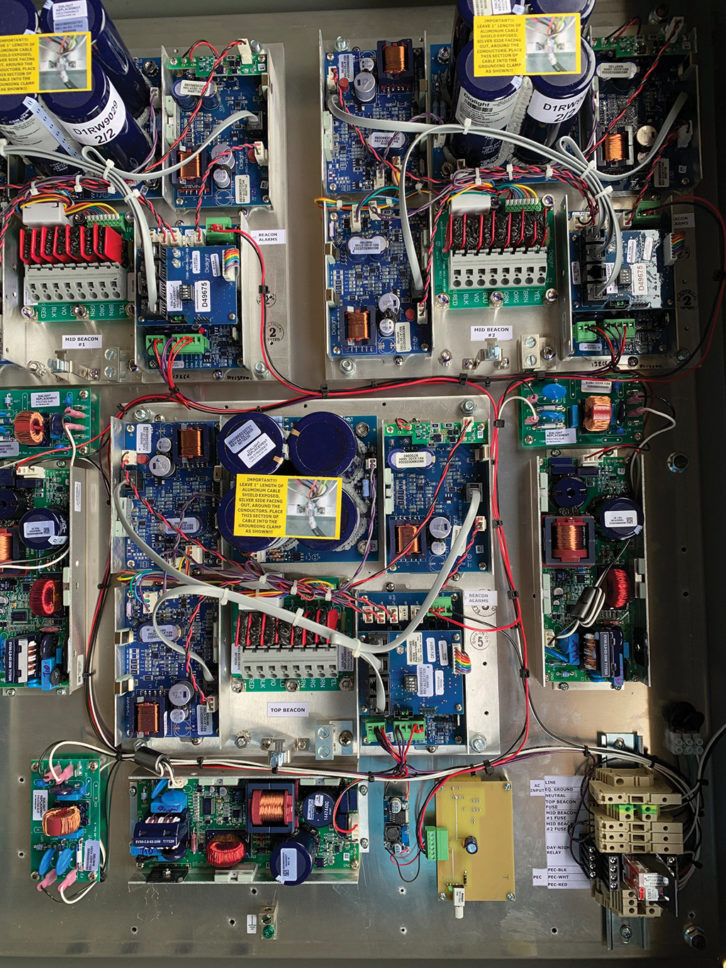

Since then, I’ve become a believer in LED tower light systems (and I’m speaking here of DC-powered LED systems, not hybrid or retrofit systems). I have been converting some of our oldest towers to new-technology systems. It’s amazingly easy. Beacons fit the bolt hole patterns of a code incandescent beacon, and all new wiring employing UV-rated SO cable is used to connect everything up.

A couple of years ago, the FAA began allowing the use of dual white/red systems on towers under 700 feet high, and that encompasses most of the towers in my company. It means that we can, in many cases, convert to dual red/white systems and (if the towers are galvanized) forget about painting forever. And don’t forget about the power savings, which can be significant on taller structures and multi-tower arrays.

So, the next time you find yourself troubleshooting a tower light issue … or relamping … or replacing a solid-state or mechanical flasher … consider making the move to new technology LED tower lighting. It’s the green (or maybe red) thing to do.

Cris Alexander, CPBE, AMD, DRB, is director of engineering of Crawford Broadcasting Co. and technical editor of RW Engineering Extra.