I have been the “beneficiary” of three tower “events” over the course of a 48-year career. By “event,” I mean a summary collapse of one of my FM towers. And of course, by “summary collapse,” I mean that such an event was unexpected.

Tower felled by vandals, WAEB, Allentown, Pa., 2009. Courtesy Scott Fybush

In one case, the collapse was as the result of a furious (suspected) F4 tornado, which brought our 1,500-foot (457-meter) tower down in an instant, creating, without warning, a twisted mass of metal scrap.

As is customary for many radio stations, the site was well-equipped with main and backup transmitters, main and backup antennas, main and backup STL systems and a well-maintained generator plant with a week’s supply of fuel. All this “good stuff” tends to lull management (and some broadcast engineers) into a kind of “we’re all set and have checked all the boxes” mindset and a false sense of well-being. I say to you from personal experience, that sense of well-being can come to an abrupt end when a “tower event” happens to you.

THE FIVE PS

Let me share a saying from my aviation vocation: “Prior Planning Prevents Poor Performance” — also known amongst pilots as the “Five Ps.” In the case of the tornado-initiated tower collapse, we were under (as the reader might well imagine) a great deal of stress and pressure from several levels of management to “get us back on the air.”

We really had no plan in place, having been lulled into the aforementioned false sense of security. After all, we had a solid site with good backup systems and a site which had been well maintained, so events such as an F4 tornado just don’t enter into one’s thinking — particularly after many years of trouble-free operation! It was a gut-wrenching 24 hours, no fooling about that.

As it turned out, I “rigged” a Harris exciter and Harris FM25K IPA at one of our other sites by the end of the day and got program audio to the site using some auxiliary channels on an existing STL. Also, I will not neglect to mention the physical labor of singlehandedly moving a large section of 4-inch rigid line in order to connect the “emergency transmitter” to the wideband port of the combiner at the emergency site.

By the end of the long day, we were on the air at 1,500 feet and 250 watts (what we would call a “fill-in” translator today). It was a better than white noise solution — about all it was.

I suspect the reader would rightfully consider what I just described as sort of a nightmare scenario, and yes, no kidding, it was.

I mentioned that I had three towers fall during the course of my career. One was in a small market and was so long ago I scarcely can recall much detail, but the other was, no doubt about it, memorable.

We had a tower in the Mojave Desert while I was working in L.A., which collapsed at around 11 PM on a Saturday night in the Antelope Valley (known for its impressive winds). It’s difficult to find the words to describe what I felt as I observed (with a high-powered flashlight) the 440-foot tower folded over at the 150-foot level, swaying (and groaning) in the fierce winds late at night in the desert.

Many thoughts go through your mind, such as what now? How am I going to deal with this? And, what if the remaining section of tower crashes to the ground overnight?

Such times as these are when you are certain you are the “Chief Engineer.” The lot of would-be CEs sort of “lie low” when a tower collapses. Doug Irwin and I spent the remainder of our weekend scrambling around the desert doing a bit of this and that in order to get that station back on-air.

BACK IT UP

Most importantly, what we learn from these experiences is: Nothing, but nothing, beats an alternate site you can “flip on” with a mouse click or a phone call. Even if your backup site is of significantly lower power (and coverage), it can be a huge, huge stress reducer as it serves to get you back on the air immediately.

With a backup site, spots are cleared and obligations met while you set about to plan for restoration of full service, which can take several months and even years. The “tornado tower” I spoke of took two full years to be completed such that we could occupy and use the site, due to local government red-tape (amusingly, the county assured us of a “fast track”).

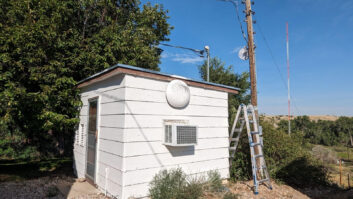

So, the point of all of this is, find some way, any way, to build up some sort of alternate site for your stations. Perhaps capital for a fully-outfitted “N+1” site that the “big boys” have isn’t in the cards for you. I have found using high-power exciters or removed-from-service exciters coupled with a no-longer-used IPA and a Barix box or old composite STL, will be as good as gold when the main site goes down.

Perhaps you’re moving to a better site but can maintain the old site as a backup. Perhaps you can mount a broadband two-bay low-cost antenna at your studio building. Be creative and get your management to realize just what can happen and ask them to consider how they will react when the tower falls and it might be two years before restoration of full service.

Dennis Sloatman is the vice president of engineering for Summit Media.